The COVID-19 pandemic has engendered unemployment as a serious challenge for the Chinese party-state from multiple angles and with manifold implications — from uncertainties in the employment front to testing the capacities of provincial administrations and anxieties of graduates entering the job market. Cognisant of the enormous task at hand, China’s Premier Li Keqiang’s Work Report at the Third Plenary Session of 13th National People’s Congress in May laid emphasis on creating 9 million jobs in urban China.

Aimed at increasing employment opportunities and raising the non-State, small business economy, he underlined the need to revitalise the street stall economy (dìtān jīngjì). To further amplify his case, on June 1-2, he even visited street stalls and vendors in the city of Yantai in Shandong province and was effusive in his praise of their contributions to the economy.

Street vending and hawking comprising food, small goods and other sundries have been an intrinsic part of China’s urban life. It has been a critical source of employment, for rural migrants, especially women; its ecosystem ranges from long-term itinerant traders to small entrepreneurs and part-time vendors, providing flexibility and mode of operation with next to no institutional constraints.

However, there has persisted ambivalence from city administrations towards this informal economy, as has been reflected in the criticisms and pushback against its revitalisation. This has also highlighted the divergences within the ruling regime on the issue. Doubts have been cast over the street economy’s efficacy and durability in stemming the enormity of the economic turbulence; the State broadcaster, CCTV, even termed it as ‘trading a watermelon for a sesame seed’.

The other set of criticisms have emanated from the administrations of big cities such as Beijing, calling them uncivilised and unhygienic, and creating a chaotic urban environment. Besides, the urban elite ascribe inferior quality to street goods due to the influx of counterfeit goods. The city administrations’ interface with street vending has oscillated between indifference and disinclination on the one hand, and resorting to violent, ham-handed measures on the other.

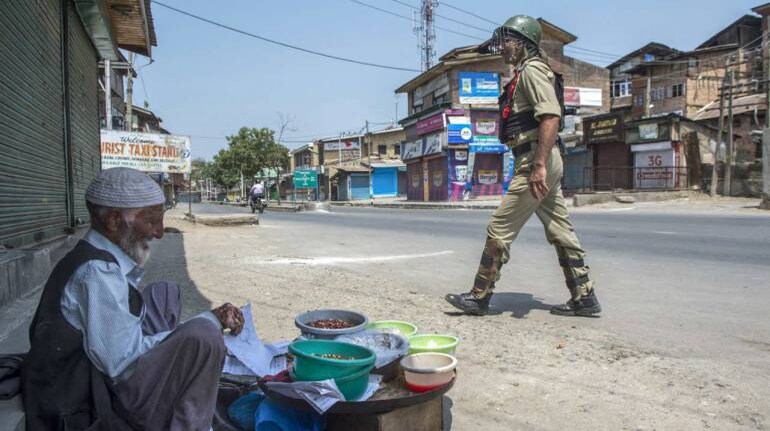

Street vending and hawking have been intrinsic to Indian cities, providing steady employment to migrants and urban poor, and forming key links to the distribution networks for food and other necessary goods, at affordable prices. Despite valorising them and recognising how essential they are to the cities’ economy, they were among those drastically affected by the lockdown.

The current government has made efforts to reach out to them, and the Pradhan Mantri Street Vendor’s Atmanirbhar Nidhi — a special micro-credit scheme, announced to provide a working capital loan of up to Rs 10,000 targeting nearly 5 million street vendors — is in this line. On September 9, Prime Minister Narendra Modi even had a virtual interaction with some beneficiaries of the scheme from Madhya Pradesh.

However, street vendor organisations and support groups have termed the scheme insufficient, and have argued for direct benefit transfers delinked from registration systems, since the lack of demand poses constraints on repayments. Further, making the complete process online has also created digital and language barriers for vendors.

At best temporary fixes, these relief measures mask systemic deficiencies that mark the precarious lives of street vendors in Indian cities, dependent on daily informal negotiations and navigations. While the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act provide legal sanctity, many states still lag behind in notifying requisite schemes under the Act, or even properly identify vendors. Further, strict imposition of the letter of the law in contrast to the spirit tends to skew the number of vendors able to do business in designated city zones and surplus vendors losing out or getting evicted.

Such in-built barriers, denial of access to urban services, along with bureaucratic detachment of urban and labour governance, and the continued reluctance of urban policymakers to involve street vendors as legitimate stakeholders, combine together to prolong their socio-spatial exclusion.

Visible in both China and India is a dominant vision of urbanity that perpetuates sanitised order and pristineness, devoid of any informal or irregular spatial practices. The pandemic has engendered categories of essential and non-essential work, but such convenient ideations without institutional and resource-based responses reiterate segregation and stratification in urban spaces. In short, street vendors, like other low-wage migrant workers, continue to be ‘strangers in the city’ in both countries.

P K Anand is a Research Associate, at the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi. Twitter: @anandpkrishnan. Views are personal.

Discover the latest business news, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!